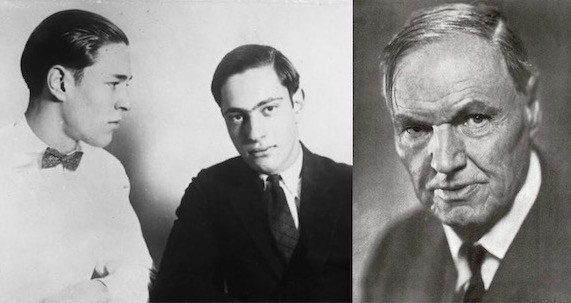

Long before Claus Von Bulow or OJ Simpson, in 1924, two Chicago teenagers committed what was called at the time, “The Crime of the Century,” only to be spared by the efforts of the greatest defense attorney in American history.

During their scouring of the Wolf Lake area, police detectives questioned the game warden of the forest preserve that was located nearby about any recurring visitors to the location. One of the names he revealed was that of Nathan Leopold, Jr a nineteen year old ornithologist and recent Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Chicago, currently taking a class at the University of Chicago’s law school. On Sunday morning, May 25, two policeman were sent to Leopold’s home to pick up the teenager for questioning, the house coincidentally in the Kenwood section near both the Harvard School and Bobby Franks’ house. Leopold had plans for a date that Sunday and was initially resistant to coming down to the precinct, but the police assured him that their captain just wanted to ask some routine questions and if he brought his car he would be back in no time.

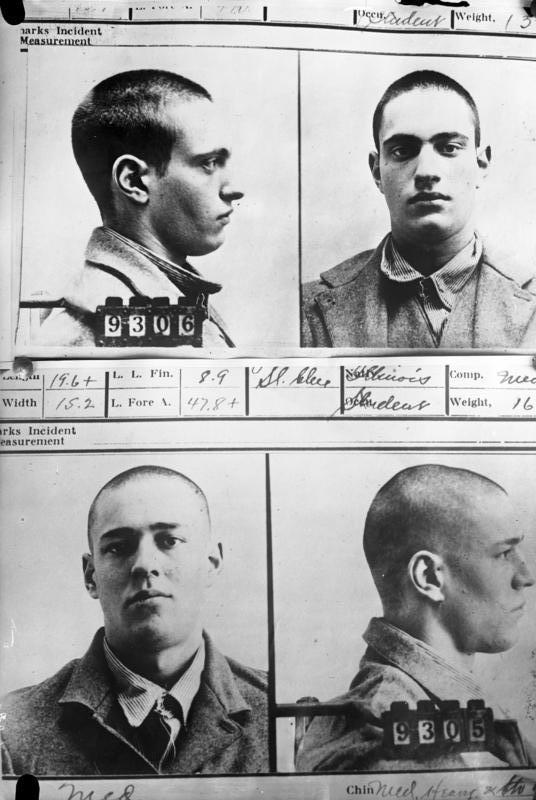

Once Richard Loeb’s name was mentioned he also was brought to the LaSalle, placed in a separate room and questioned until the early morning hours. He claimed he left Leopold around dinnertime and mentioned nothing about picking up girls, an obvious contradiction that was certainly suspicious. The next morning, Leopold and Loeb found themselves in custody, in separate police stations, Leopold at Crowe’s headquarters in the Criminal Courts Building, Loeb at a nearby precinct house.

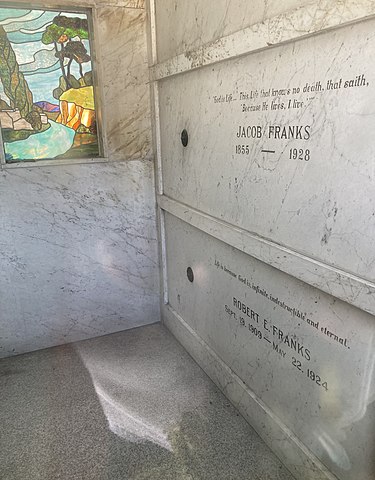

At the Franks’ house, as the dinner hour approached, Bobby Franks’ parents began to wonder where their son was. Jacob and Flora Franks were the type of typically wealthy family that populated the Kenwood neighborhood. Jacob Franks’ wealth initially stemmed from a pawn shop he inherited from his parents known as Franks Collateral Loan Bank. Franks eventually diversified his business interests, first into separate watch and watch case manufacturing companies and then into various real estate and stock investments which generated a net worth of at least 1.5 million 1924 dollars, equivalent to about 27 million dollars today.

. Because of the incredible public and media interest generated by the death of Bobby Franks, the Franks family decided to hold a small, private funeral service in their home as opposed to what might become a public circus. The Franks family were converts to Christian Science from Judaism and the affair consisted of various readings and hymns before a police escort accompanied the Franks procession to Rosehill cemetery, the pallbearers all fellow students from the Harvard School.

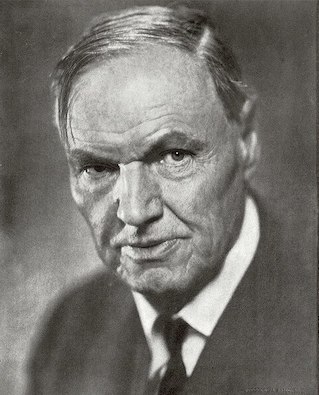

Understanding his nephew’s predicament, Jacob Loeb decided to reach out to an even more prominent individual, Clarence Darrow. By 1924, Darrow was nearing the conclusion of one of the most illustrious and controversial legal careers in US history. Starting from a small law practice in the tiny Ohio town of Andover, Darrow eventually made his way to the city of Chicago where he became famous and frequently vilified for representing various labor officials like Eugene Debs and Big Bill Haywood. A 1911 scandal involving a Los Angeles bombing case which resulted in Darrow negotiating a plea deal and accusations of jury tampering via bribery alienated the attorney from organized labor. Darrow then switched to criminal and civil defense, mostly involving defendants facing the death penalty. In over 100 cases, Darrow had only one defendant executed and that was when he joined the defense only for the penalty phase of the trial. Despite a practically disheveled appearance, Darrow’s quick legal mind and remarkable eloquence during impassioned closing arguments made him the most famous trial lawyer in America.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS