In 1925, a diphtheria epidemic threatened to wipe out the town of Nome, Alaska. Hear the incredible story of the men and dogs who saved the day.

Seppala was employed by Hammon Gold as its main dog driver and the supervisor of freight logistics into the remote areas and mining camps that the company operated. But Seppala was also known as the premier dogsled racer in the region having won numerous competitions that were a high profile Alaskan pursuit. A Norwegian and a friend of Jafet Lindberg, he emigrated to Nome in 1900, at the height of the Gold Rush that established the city.

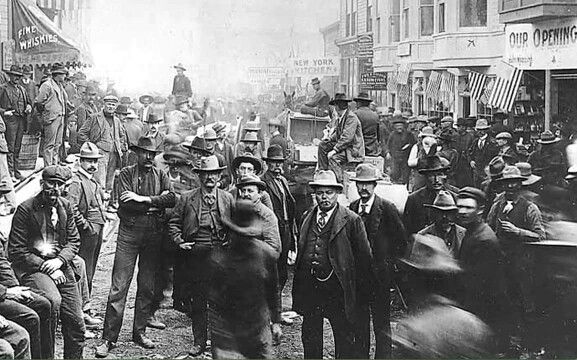

The establishment of a town in such a remote and forbidding location was actually an unplanned spontaneous event that resulted from gold being discovered in the area in mid-September, 1898. Rich deposits of the metal were discovered initially by three individuals who were eventually nicknamed the Three Lucky Swedes, Eric Lindblom, John Brynteson and Jafet Lindberg who was actually Norwegian. This group located these valuable sites in the Anvil Creek and Snake River waterways a few miles off of the coast of the Bering Sea. They legally registered their claims before word of the find became public knowledge elsewhere. However, news of this discovery quickly made it to the outside world and especially to the Klondike region where a previous 1897 gold rush had drawn over 100,000 potential prospectors.

To fill out the new team of drivers Summers contacted another one of his employees, a dog driver who also worked for Leonard Seppala, Gunnar Kaasen. Summers told Kaasen to put together another team and head for the village of Bluff, about forty miles east of Nome. When he got to Bluff he was supposed to get the roadhouse keeper there, Charles Olson, to put together his own team and head 25 miles east to the town of Golovin and wait there. Kaasen was not completely surprised by Summer’s request to assemble a team. Before his boss Seppala left, he made precautionary recommendations to Kaasen as to how to position another subsequent team. Kaasen went along with these recommendations placing the dog Fox as one of the leads. But for the other dog he chose an animal that Seppala did not particularly hold in high esteem, an unusually colored Siberian who was solid black except for a white right paw. The dog’s name was Balto, named after an associate of Norwegian explorer Fritdtjof Nansen. At the time, Kaasen did not think about the choice very much. He had always liked working with the dog and figured that the animal could certainly get the job done. Once the run was completed and the serum got to Nome what difference would it make anyway?

The serum relay remained a huge story across the United States with local journalists getting hired by national wire services to provide eyewitness accounts. Only hours after his actual arrival, Gunnar Kaasen reenacted his arrival, ambling down the main streets of Nome for photographers and motion picture cameras. Newspaper articles focused on Kaasen as he was the only participant present and because journalists wanted to focus on one dog, Balto was anointed as the main canine hero of the serum run.

During his successful racing career, Seppala’s lead dog was named Suggen and this part Malemute, part Siberian huskie subsequently sired many puppies for Seppala. By 1925, Suggen had been replaced by his son Togo, a diminutive animal, initially a runt believed too small to have any future as a sled dog. Named after the victorious Japanese admiral at the battle of Tsushima, at age six months, Seppala gave the dog away, its new owner maintaining the canine as a pet. Within a few weeks, Togo escaped from his new home by leaping through a glass window and returning to Seppala’s kennel, a journey of several miles that impressed the dog trainer enough to prompt Seppala to keep the dog. But the puppy proved difficult to train, frequently breaking out of the kennel to follow Seppala when left behind and off of the team. On the trail, Togo would distract the group to the extent that Seppala finally decided to harness the dog, if only to control him. Immediately, the younger dog responded, able to keep up with older, larger animals on runs that frequently totaled seventy-five miles a day. Seppala came to believe that Togo, 48 pounds at his heaviest weight, was a once in a life time prodigy that he quickly trained and ultimately designated as a lead dog. By 1925, Togo, aged 12, was so respected by Seppala that he frequently placed the dog by himself, with a long lead in front of the other dogs.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS