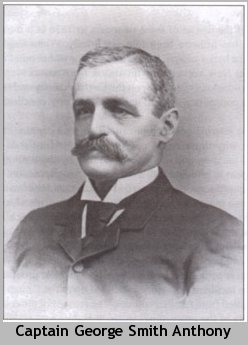

Captain George Smith Anthony and The Voyage of the SS Catalpa

In 1874, rebel leader John Devoy received another letter from Fenian prisoner James Wilson that he chose to read aloud at a national meeting of the Clan Na Gael. Part of it read:

In 1874, rebel leader John Devoy received another letter from Fenian prisoner James Wilson that he chose to read aloud at a national meeting of the Clan Na Gael. Part of it read:

“Think that we have been nine years in this living tomb since our

first arrest and it is impossible for mind and body to withstand the

continual strain that is upon them. One or the other must give way

…We think that if you forsake us, then we are friendless indeed.”

This missive, the “Letter From the Tomb”, compelled the Clan to understand that to rescue the military Fenians was their moral imperative. Devoy was officially urged to devise a plan of escape and he immediately proceeded to Boston and a meeting with John O’Reilly, the only man ever to successfully escape from an Australian penal colony. O’Reilly was still in touch with members of the New Bedford, Massachusetts whaling community, including some of the former members of the crew of the Gazelle. This close knit group quickly sold Devoy on the idea that any rescue attempt should also try to fund itself by engaging in a legitimate whaling expedition. They also agreed that there was only one man for the job, Captain George Smith Anthony.

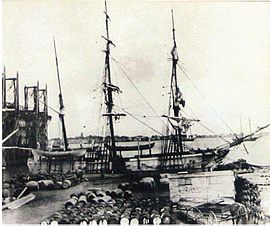

Recruiting Anthony was merely a start. Devoy, O’Reilly and Richardson began to scour New England for a suitable ship. Although the Clan Na Gael had secretly raised some money from a national base of contributors they were still short of the purchase price of an appropriate vessel. It took Richardson fronting thousands of dollars and another Clan Na Gael member, James Reynolds, mortgaging his home to provide the funding for the purchase of the ”Catalpa”, a ninety foot merchant ship that had recently returned from the West Indies. In March of 1875, the ship was towed to New Bedford where Captain Anthony could personally supervise its repairs and reworking as a whaler.

By the end of April, a twenty-two man crew had been selected with only one man, Dennis Duggan, aware of the true mission of the Catalpa. Duggan, Irish, was also a carpenter by trade so he would not arouse the suspicions of customs officials about any atypical crew aboard a whaler. On April 30, 1875, Captain George Anthony raised anchor in New Bedford and began the first leg of the mission to rescue the six Irish rebels.

In January of 1868, after three months at sea, their prison ship reached western Australia. On the tenth, it dropped anchor in Fremantle and the prisoners were transported to the jetty at Victoria Quay. From there they marched through the town to the Fremantle Gaol, a forbidding stone edifice with a practically medieval appearance. Nicknamed “The Establishment” this prison confined over three thousand human beings, fifteen per cent of the western region’s twenty thousand inhabitants. Escape was considered impossible. If a convict even made it outside of the walls of Fremantle Gaol, he would have to circumvent thousands of miles of shark infested ocean or an equally lengthy trek through the desert like conditions of the Australian bush country. He would probably die of thirst before aboriginal trackers found him and dragged him back to be hanged in the prison yard. The military members of the Fenian group were placed in one man cells that were three feet wide, seven feet long and nine feet high. Here they were doomed to service on a work gang, eventual death and burial in an unmarked grave along some Australian road.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS