The triumph, tragedy and bizarre secrets of one of the 20th century’s most prominent figures.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The triumph, tragedy and bizarre secrets of one of the 20th century’s most prominent figures.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The books used to compose this podcast included:

“Loss of Eden,” by Joyce Milton

“The Flight,” by Dan Hampton

“Forward From Here,” by Reeve Lindbergh

The intro music in part one and outro music in part two is: “Helium,” by Track Tribe.

The outro music in part one and intro music in part two is: “No Indication,” by Track Tribe.

In 1770, the French people greeted Austrian Marie Antoinette as the beautiful and future French queen. Twenty-three years later they guillotined her as the most reviled woman in France.

In Europe, with most political powers ruled by monarchies, the best method of insuring a stable alliance with another ruling dynasty was through marriage. Maria Theresa aggressively forged alliances with the French Bourbons dynasty through marriages of her daughters Maria Amalia and Maria Karolina to the rulers of the Italian duchies of Parma and Naples. But her most ambitious union was reserved for her youngest daughter, Maria Antonia.

Maria Theresa gave birth to sixteen children, unusually thirteen survived into at least early childhood, including the second youngest, Maria Antonia. As the house of Hapsburg was decidedly Roman Catholic all ten of the Empress’ daughters had the first name of Maria, an acknowledgement of the Virgin Mary. Maria Theresa was a workaholic who spent most of her days focused on the affairs of state, but she closely supervised the tutors and nannies who were responsible for her children’s upbringing and education. Her strong work ethic and stubborn determination were fortunate personality traits. Only months after her ascension, many of the European monarchs who had formally agreed with her father to recognize her as his heir renounced this agreement, perhaps sensing weakness. Frederick the Great’s 1740 invasion of the Austrian province of Silesia set off an eight-year war that eventually involved all of the great powers of Europe. It was not until 1748 that diplomacy resolved this conflict, and firmly established Maria Theresa as de facto Holy Roman Empress and Archduchess of Austria, but Prussia and Frederick remained hostile and within eight years another war broke out. The Seven Years War strengthened Austria’s profile in Europe but the immense cost of this conflict convinced the Empress that diplomacy was a much more reasonable way to maintain political power and preserve her domain.

In Europe, with most political powers ruled by monarchies, the best method of insuring a stable alliance with another ruling dynasty was through marriage. Maria Theresa aggressively forged alliances with the French Bourbons dynasty through marriages of her daughters Maria Amalia and Maria Karolina to the rulers of the Italian duchies of Parma and Naples. But her most ambitious union was reserved for her youngest daughter, Maria Antonia. Approximately the same age as the heir to the French crown, the grandson of France’s King Louis XV seemed an obvious match and serious negotiations began between the two courts to make this wedding happen. A special tutor, the Abbe Jacques de Vermond was brought to Vienna’s Hofburg palace from France to improve the teenager’s language skills and overall social polish, underlining the serious nature of the discussion. A French dentist even surgically and painfully straightened her teeth. But this was only the beginning of a process demanded by Louis XV, that focused obsessively on the physical appearance of France’s potential queen. Louis’ womanizing exceeded that of even his royal contemporaries, the famous mistresses Madame Du Pompadour and Madame Du Barry among the dozens of women achieving notoriety during his fifty-nine-year reign.

In April of 1770, Maria Theresa packed off her daughter as well as the Abbe de Vermond, by then subtly cultivated as the Empress’ eventual eyes and ears once the marriage took place and Maria Antonia began a journey that proved emotionally overwhelming. This trip started on April 21, 1770, in the main courtyard of Vienna’s Hofburg, the sprawling palace of Austrian emperors and in this case the Empress, Maria Therese. The empress’ daughter was placed in a magnificent gilded carriage, saluted by a crowd of patrician well-wishers and Swiss Guard ceremonial rifle volleys, and then sent off while all of the church bells of the city pealed in a congratulatory farewell.

Although Marie’s Austrian royal family lived in the sprawling Hofburg complex and also constructed the impressive Schonbrunn Palace on the outskirts of Vienna, probably nothing prepared her for the grandiosity of the seat of the French monarchy. Built by Louis XIV as not only a statement of his national superiority and absolute power, the king also wished to contain all of the members of his court under one roof. Hundreds of apartments were provided for those members of French society who were prominent enough to merit such status. But Louis’ ostensible generosity concealed an underlying motive, that of keeping the nobility under his literal eye and stripping them of any political power or even ability to unite against his absolute rule. Thousands of inhabitants lived within the palace, which could hold as many as ten thousand residents but typically housed between two and four thousand occupants.

Louis XVI also attempted to remove any legacy of the former mistress, the Madame de Pompadour, by officially presenting his wife the Petit Trianon, a small chateau on the grounds of Versailles, formerly built and occupied by De Pompadour. Initially, the ascension of the new king and his beautiful wife was greeted by the public with happiness and the young couple was popular, the staggering deficits and disastrous foreign policy of Louis XV rendering him a bad memory. It was hoped that a new reign would also bring new attitudes and a new direction.

Marginalized politically, with her husband’s chief advisors hostile to Austria, Marie Antoinette immersed herself in a pastime meant to underline her status as the court’s most important female. She began the practice of weekly masked, costumed balls, centered around various themes, her costumes sparing no expense and distinguishing her from her guests with spectacular clothing. Her husband, perhaps guilty at his ongoing sexual disinterest allowed her to spend fantastic amounts on her wardrobe and the parties themselves which frequently lasted until dawn. These exercises were undertaken to at least publicly maintain the façade that Marie Antoinette enjoyed great influence with the king and she hoped over time to regain the same political prestige as that of Louis XV’s mistresses.

Mortality suddenly intervened in the spring of 1774 to permanently change the relatively vapid routine of the heir and his wife. On April 27, Louis XV went hunting with his entourage but suddenly felt too sick to even leave his carriage. By May 3 even he acknowledged that the red lesions on his body were indicative of smallpox. The king lasted another week, many accounts stating that in his final hours he uttered the phrase “Apres moi, le deluge,” After me, the deluge, a supposed acknowledgement that the financial excesses and utter governmental mismanagement of France could only result in catastrophe. Like many storied quotations, this one most likely never occurred but it should have and it was a fitting admonition for especially the now Louis the XVI and Marie Antoinette.

On the 19th of August, the Commune removed all eight non-royal members of the entourage. Most were eventually released unharmed, one, Marie, Princess de Lamballe, a close friend and confidante of Marie Antoinette, who had faithfully remained with the Queen during her recent ordeals was dragged before an impromptu September 3rd Commune tribunal at her new prison location. These tribunals, a violent response meant to liquidate any prisoners formerly associated with the monarchy, were convened as a result of the Austro-Prussian offensive that initially made great progress in its intent to overturn the Revolution. Asked to swear loyalty to the new government and to denounce the King and Queen, the Princess de Lamballe affirmed the former but refused the latter, stating that whether she died then or shortly thereafter was not worth her honor and dignity. Released into the courtyard she was beaten and stabbed to death by a mob assembled to execute those condemned by the tribunal with the words, Let them go,” the victim unaware that this was actually a death sentence. The Princess’ body was beheaded, disemboweled and her remains paraded through the city on pikes, this procession reaching the Temple with the intent to display this grisly artifact to the King and Queen. Although she did not see this display, Marie Antoinette fainted upon hearing about the fate of her former friend. This killing, and hundreds of others that occurred during this incident became known as the September Massacres.

Convinced that he was on the verge of a great political restoration and even deluded enough to believe that Marie Antoinette was physically attracted to him, De Rohan now reached out to the jewelers, who were also blinded by their zeal to unload the necklace. With, unbeknownst to him, forged letters in hand from the purported Marie Antoinette, requesting that the Cardinal act as her representative, a deal was negotiated whereby the necklace would be paid for in installments. Of course, the transaction was to occur amidst the utmost secrecy, a condition De La Motte could not emphasize enough. The necklace was secured by the Bishop, he then was instructed to turn it over to an individual described as a valet of the Queen, in fact Nicholas de la Motte, who hastily fled to London. By the time the alleged count arrived in England, the diamonds had been pried out of their settings, many damaged during the process, but still able to be fenced. Jean De La Motte briefly fended off both the Cardinal and the jewelers by forwarding token sums as “installments,” but by July of 1785, with Marie Antoinette having never worn the elaborate necklace publicly or reaching out to the Cardinal to acknowledge his noble deed and De La Motte no longer making any installments, both parties decided that it was time to act. A letter dictated by the Cardinal, and signed and sent by Boehmer was meant to subtly remind the Queen of both her new acquisition and financial obligation. But Marie Antoinette was so baffled by the July 12th letter that after discussing it with her first lady in waiting, Henriette Campan, she burnt it, thinking only that Boehmer was somehow trying to peddle her some more jewelry. Disturbed and now alarmed by any lack of response Boehmer waited until the 3rd of August before showing up at Henriette Campan’s residence. Campan was so shocked by first his insistent claim that the queen had made such a byzantine purchase and the details surrounding those involved, that she decided against informing the queen herself, advising that Boehmer should take the matter up with the Minister of the Royal Household.

In 1775, the Comte and Comtesse de Polignac, like many other members of the French nobility, visited Versailles to pay their respects to the new king and queen. Although aristocratic the couple had fallen on hard times and were deeply in debt. The Comtesse, Yolande Gabrielle de Polignac, was extremely pretty and immediately ingratiated herself with Marie Antoinette, who encouraged her to spend more time at court. The Polignac debt was quickly taken care of by the king and upon the birth of Marie’s first child, Gabrielle was named governess, a lucrative official position. The post also came with a palace apartment, in this case a luxurious spread of thirteen rooms. Her husband Jules de Polignac also received several paid court positions as well as the title of Duc de Polignac. Other family members received considerable pensions paid out for virtually no responsibility. Because Marie enjoyed her company, Louis XVI was enthusiastic about such expense, if only to placate his wife. When Gabrielle’s daughter married into another noble family, the king paid the dowry, equivalent to millions of dollars today. Marie Antoinette’s affection for her best friend was further underlined by the assignment of one of the cottages constructed in the faux village of the Petit Trianon to Madame de Polignac, in an area that was physically off limits to all but the most prominent members of the French court. Gabrielle’s new son-in-law was immediately named captain of the guards, her brother in law ambassador to Switzerland. The de Polignac’s became quite unpopular at court, they did their best to exploit their new positions, and isolated other courtiers from Marie, as no one could enter her inner circle without the Comtesse de Polignac’s approval. Their initial lowly status made their receipt of such largesse a point of deep resentment amidst the intensely status conscious world of Versailles. This animus prompted external gossip about such extravagance, the De Polignac’s hated by the public as much as Marie Antoinette herself. With no guarantee of their personal security, the entire extended family fled the country on July 15, one day after the storming of the Bastille.

But neither Marie or her husband would be respected as dutiful monarchs if the continued sexual reticence of the king prevented any progress in the process of producing an heir. When Louis XVI’s younger brother married and produced a son in 1775, this only increased the pressure on the sovereigns to behave accordingly. This issue became so serious especially for the Austrian court because they would lose any connection to the French throne if Marie Antoinette did not give birth, that it was decided that Maria Theresa’s son, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor and heir to the Austrian throne would visit his sister to attempt to get to the bottom as to what exactly was holding up the process. Although happy to see any relative, the Queen was also apprehensive as her elder brother frequently could be insensitive and critical and had already admonished her in numerous letters over the current situation. In April of 1777, travelling incognito as Count Falkenstein to avoid any embarrassing attention over his mission, the Emperor also resorted to a plain wardrobe and an absence of medals and decorations. To avoid the time wasting rituals of Versailles, he stayed in a nearby hotel, maximizing his interaction with both his sister and Louis XVI. He spent a great deal of time with his sister but also had some frank discussions with the king as to what exactly was required in this situation. Whatever difficulty or apathy that formerly plagued the king subsided and shortly after her brother’s visit, Marie Antoinette was able to report to her mother that more than seven years after his wedding day, Louis XVI successfully consummated his marriage.

Maria Therese was able to survive the excesses of the Revolution, eventually exchanged for various French dignitaries imprisoned throughout Europe. France would then undergo the Reign of Terror, the ascendance of Napoleon and the Napoleonic wars that resulted in a restoration of the Bourbon dynasty in 1814. Louis XVI’s brother, the Comte de Provence was crowned Louis XVIII after Napoleon’s exile to Elba. His reign interrupted by the one hundred days and Waterloo, he ruled until 1824, when he was succeeded by the Comte D’Artois, Louis XVI’s youngest brother as Charles X, a ruler so odious and reactionary that he prompted a second popular revolution, an event that caused his abdication. Officially, his son, known historically as Louis XIX, reigned for twenty minutes, while Marie Therese, the daughter of Marie Antoinette, now married to the prospective king of France, begged him not to abdicate. He refused, signing off on any claim to the throne, but in this final flickering twilight of the French monarchy, Marie Antoinette’s daughter reigned briefly as the last Queen of France.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

In 1770, the French people greeted Austrian Marie Antoinette as the beautiful and future French queen. Twenty-three years later they guillotined her as the most reviled woman in France.

The affair of the Diamond Necklace had its origin in a piece of jewelry that was commissioned by Louis XV in 1772 and meant as a gift for his mistress, the Madame Du Barry. He requested that the royal jewelers Charles Boehmer and Paul Bassenge create a diamond necklace that exceeded anything previously produced. On spec, the two men took great pains to assemble a creation that incorporated a great number of exquisite diamonds in a staggeringly large and ornate necklace. Called, “The Slave’s Collar,” and consisting of over 2800 carats of diamonds, the worth of this necklace today has been estimated to be as high as one hundred million dollars. Unfortunately, the King died before this accoutrement could be finalized, the jewelers now stuck with a very expensive piece of jewelry and an extremely small pool of potential buyers, the most obvious Louis XVI. But twice, in 1778 and again in 1781, for one reason or another both the King and Marie Antoinette declined to purchase the necklace. Unsold, this became the basis of an elaborate confidence scheme hatched by a socially and financially ambitious woman who called herself the Comtesse Jeanne de la Motte.

By late 1784, Jeanne had ingratiated herself as the mistress of the Cardinal de Rohan, not only a member of the powerful de Rohan noble family but a former diplomat deployed in Vienna to the court of Maria Theresa. Unfortunately, his dissolute lifestyle and anti-Austrian bias earned him the antagonism of the Empress, who in turn delivered her opinion of the Cardinal to Marie Antoinette. Upon Louis XVI assuming the throne, De Rohan, most likely upon the urging of the Queen, was hastily recalled. Understanding that the Cardinal was desperate to improve his status within the French court, Jeanne de La Motte convinced De Rohan that she was well connected to especially Marie Antoinette. In fact, through a forger, fellow huckster and also feigned aristocrat Armand Retaux de Villette, Jeanne was able to access the French Court. She further convinced de Rohan that the Queen had officially acknowledged her and that Marie Antoinette held her in high esteem. De Rohan then began what he thought was a correspondence with the Queen, receiving letters in return that were actually forged by Retaux de Villette. Blinded by his ambition, De Rohan did not hesitate when Jeanne began asking for loans and even produced signed letters which requested that he help the Queen secretly acquire the, “Slave’s Collar,” to avoid public and even Louis XVI’s awareness of such an exorbitant purchase, an acquisition that might inflame hostility over royal expenditures even further. To add further credibility to the scheme, De La Motte and Retaux de Villette staged a nocturnal, secret liaison between the Cardinal and a woman he thought was Marie Antoinette. In fact, the two confederates hired a prostitute who resembled the queen, Nicole d’Oliva, the three arranging to meet the Cardinal in a remote corner of the gardens of Versailles. In the darkness, d’Oliva, dressed fashionably, approached the Cardinal, handed him a rose and breathlessly intoned, “You know what this means, the past will be forgotten” before quickly and stealthily retreating.

Convinced that he was on the verge of a great political restoration and even deluded enough to believe that Marie Antoinette was physically attracted to him, De Rohan now reached out to the jewelers, who were also blinded by their zeal to unload the necklace. With, unbeknownst to him, forged letters in hand from the purported Marie Antoinette, requesting that the Cardinal act as her representative, a deal was negotiated whereby the necklace would be paid for in installments. Of course, the transaction was to occur amidst the utmost secrecy, a condition De La Motte could not emphasize enough. The necklace was secured by the Bishop, he then was instructed to turn it over to an individual described as a valet of the Queen, in fact Nicholas de la Motte, who hastily fled to London. By the time the alleged count arrived in England, the diamonds had been pried out of their settings, many damaged during the process, but still able to be fenced.

Marie Antoinette’s son and heir, the dauphin Louis Charles, already considered by royalist emigres as the de facto Louis XVII, was treated just as brutally. After his mother’s execution, he was placed in a solitary, damp cell, fed through the bars, with little interaction with his jailers. He endured such conditions for sixth months, until a change in government allowed for the improvement of his confinement. By then he had contracted tuberculosis, the ailment which killed him on June 8, 1795, aged ten years old.

Louis XVI’s brother, the Comte de Provence was crowned Louis XVIII after Napoleon’s exile to Elba. His reign interrupted by the one hundred days and Waterloo, he ruled until 1824.

Louis XVI’s youngest brother as Charles X, a ruler so odious and reactionary that he prompted a second popular revolution, an event that caused his abdication.

Back at the Temple, Marie Antoinette was not formally told of her husband’s death but the noise and tumult from the street down below told her and her family everything they needed to know. From that day on, she received and wore black mourning clothes and descended into a hopeless depression.

On July 3rd, Marie’s status took an ominous turn when she was informed by her jailers that she was to be separated from her son. Additional Austrian victories now placed Paris in even greater danger. As a result, at two o’clock in the morning on August 2, Marie Antoinette was transferred to the Conciergerie, a much more secure and foreboding courthouse and prison. There was no attempt to spruce up her new environment or disguise its intent, the damp brick, bed, rudimentary chair and bucket toilet of a prison cell. A hapless attempt by royal sympathizers within the prison known as the Carnation plot only served to tighten the security around Marie Antoinette. From then on armed sentries remained in her cell, subdivided with a simple wooden screen which did little to protect Marie’s modesty.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The books used in this podcast included:

“Marie Antoinette: The Journey,” by Antonia Fraser and

“Queen of Fashion,” by Caroline Weber.

The intro to both parts was, “A Baroque Letter,” by Aaron Kenny and

The outro to both parts was, “Surrender,” by Asher Fulero.

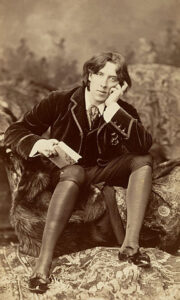

In March of 1895, Oscar Wilde enjoyed fame and fortune as one of Britain’s foremost literary figures. Only four months later he was inprisoned for the crime of “gross indecency,” convicted of violating Britain’s laws against same sex relationships. Upon his release, he exiled himself to France, his career in ruins and never saw his family again.

At Oxford, Wilde continued his immersion in the classics. The school was definitely a step up in class, his fellow students having matriculated at Eton, Harrow or similarly upper class English preparatory environments. Many were also comparatively much wealthier than the modestly affluent Irish native. A later journalistic account described him as initially, naïve, embarrassed, with a convulsive laugh, a lisp and Irish accent.

Wilde sailed for America, arriving in New York on January 2, 1882. Oscar, who received a great deal of attention in London’s society columns, and whose tour was widely publicized in both Britain and the US, was swamped by journalists, even before he was able to clear customs and disembark, the press actually hiring boats to interview Wilde offshore.

Wishing to represent himself as an aesthete in appearance as well as philosophical perspective, Wilde greeted the press in a full length green topcoat, trimmed with fur on the cuffs and collars, a similarly colored and trimmed rounded green hat on his head, hair much longer then was typical. A large collared shirt with light blue tie was visible underneath this outer layer. He also wore a large seal ring with a classical Greek profile.

Oscar Wilde also remained focused on Constance Lloyd. In Dublin, for a series of lectures, he was invited to the home of relative’s of Constance’s mother, Adelaide Atkinson Lloyd. There, Oscar and Constance spent time together and socialized for the next few days, Constance attending both of Wilde’s Dublin lectures. On November 25, the couple were left alone in the drawing room of the Atkinson home, the same room where Constance’s father proposed to her mother. Here, also Oscar Wilde proposed to Constance Lloyd. She accepted immediately and was described as, “insanely happy.”

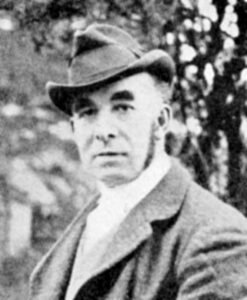

But just as Wilde reached the heights of public popularity, his private life resulted in his complete personal ruin and professional destruction. Although his vow of celibacy applied to his relationship with his wife, it did not preclude Wilde from consorting sexually with men, on a frequent basis that included what were termed, “rent boys,” young, working class males typically in their late teens. Wilde was also emotionally involved with Lord Alfred Douglas, nicknamed Bosie, a student at Oxford when Wilde was introduced to him. The two began a tempestuous lengthy relationship that was also quite indiscrete.

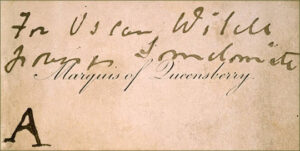

On February 28, 1895, Wilde entered a private club of which he was a member, the Albemarle Club. He was hailed by the doorman, who handed him an envelope, stating that the enclosed card was dropped off ten days earlier. Inside was a card embossed with the Marquess of Queensbury’s name and written in script, “For Oscar Wilde- posing Somdomite,” the last word misspelled but written with clear intent. Only the card was delivered, it was judiciously placed in an envelope by the doorman and could have easily been seen by staff, as well as members, which included women.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

In March of 1895, Oscar Wilde enjoyed fame and fortune as one of Britain’s foremost literary figures. Only four months later he was inprisoned for the crime of “gross indecency,” convicted of violating Britain’s laws against same sex relationships. Upon his release, he exiled himself to France, his career in ruins and never saw his family again.

Unfortunately, their reunion was so successful that both men began contemplating running off to Naples, the consequences be damned. Robert Ross and various other associates and friends of Wilde soon heard about this development and were all uniformly dismayed. Wilde was literally living off his wife’s allowance, funds that would be jeopardized if the news of his rekindled relationship with Bosie became known to her and especially her attorneys. Even so, he needed to borrow money just to get to Naples by train, leaving this important fact out of any discussions he had about his reasons for heading to Italy.

Robert Ross’ belief that Wilde’s literary reputation would eventually be reconstituted occurred faster than even he anticipated. By the beginning of the 20th century, various critical analyses and biographies and accounts of Wilde’s life appeared to great interest. His plays never really disappeared for any length of time, their popularity in British regional theater continued and all of Wilde’s theatrical works returned to popularity internationally as the century progressed. By 1908, Ross had successfully repurchased all of Wilde’s copyrights that were sold off during Oscar’s bankruptcy proceedings. These rights were then returned to Wilde’s sons.

John Sholto Douglas, the ninth Marquess of Queensberry. Aggressively masculine and a sportsman, as opposed to his sons, the elder Douglas, is credited with creating what are known as boxing’s “Queensberry Rules,” the ten basic rules that govern boxing even today. Despite great wealth, Douglas was extremely hostile, and possibly mentally ill.

Although his wife also restored a modest allowance of ten pounds a month upon hearing of his break with Douglas, Wilde received the news that she died on April 7, 1898 after a botched operation to relieve her paralysis. She was buried in Genoa, her gravestone using her newly assumed name of Holland with no mention of Oscar Wilde.

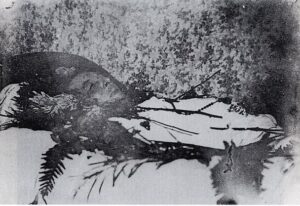

Finding Wilde borderline delirious and hearing that he had no more than days to live, Ross then went to the nearest Catholic church and brought back an Irish priest who quickly went through the official ceremony of converting Wilde to Catholicism. Ross also sent cables to Frank Harris and Alfred Douglas, warning them of Wilde’s current state. By the morning of November of November 30, Wilde had lost consciousness and was completely unresponsive. He died that afternoon.

Ross also transferred Wilde’s remains from Bagneaux to the more prestigious Parisian cemetery at Pere Lachaise, already the resting place of Chopin, Balzac, Moliere and eventually Sarah Bernhardt, Edith Piaf and Jim Morrison. Ross also collected funds for a magnificent sculpted abstract sphinxlike creature, requesting that the artist Jacob Epstein include a compartment for the internment of Ross’ own ashes, a request that was not fulfilled until 1950, 32 years after Ross’ death at age 49 of a heart attack. Epstein’s monument is perhaps too magnificent, it was repeatedly vandalized by lipstick kisses until cemetery authorities cleaned it and installed plexiglass to prevent such future vandalism.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The books used to compose this podcast included:

“Oscar Wilde,” by Richard Ellman.

“Oscar Wilde, A Life,” by Matthew Sturgis

“Oscar Wilde: The Unrepentant Years,” by Nicholas Frankel

The intro for Part One and outro for Part Two was, “Floating Home,” by Brian Bolger

The outro for Part One was “French Fuse,” by Somewhere Fuse.

The intro for Part Two was, “Hopeless,” by Jimena Contreras

Martyr and Saint, Savior of France, National Icon, All by the Age of Nineteen

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Paul Gauguin, the Bitterness and the Beauty

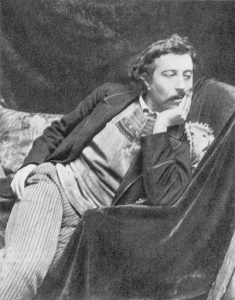

From his very first days, Gauguin’s life was filled with a volatile instability that must have affected his development. He was born in Paris on June 7, 1848. His father, Clovis, was a journalist, his mother, Aline, the daughter of Flora Tristan, a seminal feminist writer of the early nineteenth century. Aline’s father had been imprisoned for the attempted murder of Flora, an indication of the chaos surrounding Gauguin’s immediate family. Flora Tristan died in 1844, and in 1847 Aline married Clovis and soon settled down to married life and the birth of a daughter in 1847 and Paul in 1848. But the political unrest of Paris forced the young family to think about heading into exile.

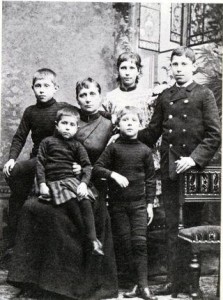

It was at the home of Gustave Arosa that Gauguin, in November of 1872, met two female guests, travelling from Denmark. One of these woman, Mette-Sophie Gad, was immediately attracted to Gauguin and a yearlong courtship began. Mette was no great beauty, but all accounts indicate that she had a great deal of personality and a practically masculine outlook that could handle the rough edges of an ex-sailor. A year later the couple would be married and Mette would rapidly become pregnant, Paul’s stock market employment providing a comfortable lifestyle.

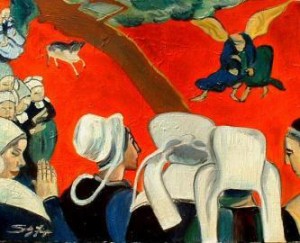

With the death of Theo Van Gogh and the realization that none of his compatriots would leave France for the exotic destinations that he continually fantasized about, Gauguin became fixated on a newer and even more remote destination: Tahiti. Again he held out for a major sale and a large check that would get him out of France. He had maintained this fantasy for decades but this time his growing reputation and a newspaper article published the day before a planned sale at the prestigious auction house at the Hotel Druout insured that his paintings would generate a substantial sum. In all thirty paintings were sold on February 23, 1891, including “Vision After the Sermon” and the portrait “Beautiful Angela” which was purchased by Degas.

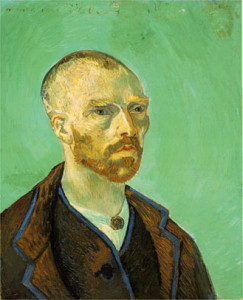

Vincent Van Gogh had spent the summer writing to all of the artists of Pont-Aven, imploring them to participate in a “colony” in Arles, where he had already relocated. Gauguin repeatedly put him off by claiming that he would have to wait until he sold some paintings and raised the money to pay off his debts in Brittany. But when Theo Van Gogh sent him some money and promised more if he would merely agree to join Vincent in the south of France, Gauguin acquiesced. The overjoyed artist sent him a remarkable, jade green self portrait dedicated to “mon ami Paul” and typically began to fixate on when Gauguin would arrive or if he would even show up at all. Thus the stage was set for one of the most notoriously tragic incidents in art history.

A sequence of events in late December brought about Gauguin’s inevitable departure. As the weather kept them painting indoors, Van Gogh returned to his familiar motif of sunflowers, Gauguin painted a portrait of Vincent at work. The result horrified and angered Van Gogh. “It is certainly I, but it’s I gone mad!” That night at a cafe an argument culminated in Van Gogh throwing a glass of absinthe at Gauguin, who dragged him home and put him to bed. Although Van Gogh tried to apologize, Gauguin responded by saying he could no longer stay because he might respond to such future outbursts by strangling Vincent.

A terrible rainy season insured that Gauguin and Van Gogh would spend most of their time shut up in the Yellow House, unable to paint outside. They spent much of their time in philosophical discussions that ultimately became hostile, Gauguin condescendingly dismissive towards all of Van Gogh’s opinions especially when it came to art.

Gauguin’s deteriorating health affected his productivity but he still would produce some of his greatest works during this time period, especially, “Two Tahitian Women”, now in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

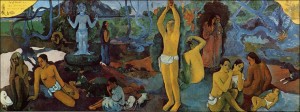

He also produced the allegorical “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? that is now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS